Thornton Wilder

A half-shoddy attempt at drawing Jackie Gleason, on set at Take Me Along, 1960. I’ll have to try again…

Three Women

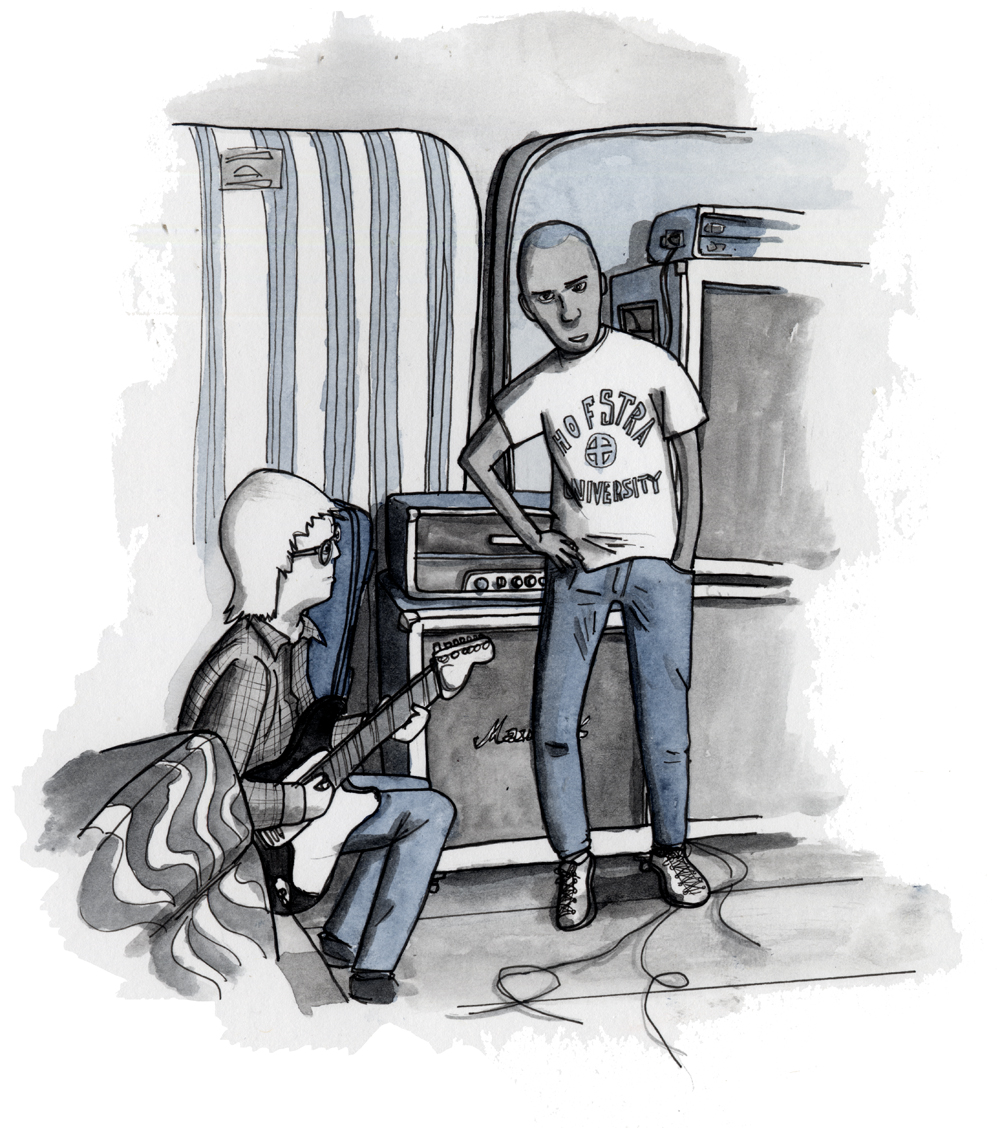

Brian Baker & Shawn Brown — Dag Nasty

The 4 Train, the 3 Train

On the Q Train

Toshiro Mifune in Sanjuro — 1962

Trying to draw the shaggy girth that is my parent’s golden retriever…

Daniel Higgs, Lungfish

The Descendents

Roddy Doyle

James Thurber

The Bark Monster

One of the lesser known specters that haunted the Hudson River Valley, the Bark Monster, or Schors Duivel, was itself based on an old Indian legend that the Dutch of New Amsterdam appropriated during the early years of the settlement. The legend, recorded in various forms (the most famous put down in Van Beveren’s The Witches of the Hudson River Valley, which I rely on here), involved a beautiful maiden, who being pursued by an amorous woodsman, took refuge in the hollow of an enchanted chestnut tree. The tree, enthralled with the maiden’s beauty, took her captive by closing up its hollow and tearing itself from its roots, becoming a creature of iron-hard bark and sharp talons, with wisps of the lovely maiden’s golden hair streaming out into the wind. The Schors Duivel, in an effort to protect its beloved from would-be suitors, would stalk the forests, searching for men to feed its jealous rage. Woe to the lone woodsman who encountered the beast. In the winter months, however, the monster, like all trees, would lose its leaves and fall into a deep slumber. If then an adventurous soul was able to find the creature’s hiding place, he would be able to peel open the bark armor of the creature and rescue the maiden, winning her hand.

In some versions of the tale, the maiden is more of a haughty temptress, relishing the death of her many suitors, and in others the brunt of the moral falls more upon the woodsman for coveting a woman who is not his to have. In any case, the myth had an effect on the vernacular of the time, with the phrase “peeling away her bark” becoming a regional euphemism for hopelessly courting an unwilling lass.

The Bark Monster

Fats Waller

Leica

Three Men

The Tale of the Icon and the Scientist

Not so many years ago, a porcelain statue was found wedged between two dusty ledgers on a storage shelf at the Thomas Pullings Memorial Maritime Library in Portland, Maine. Made of cheap porcelain and haphazardly coated with industrial pigment, it at first seemed to be nothing more than a discarded piece of bric-a-brac. But then, somebody noticed the shadows.

You may remember the media frenzy. Research teams from various scientific institutions, a group of rangy poets from the Institute for Applied Philosophy, and a Papal-appointed team of forensic investigators direct from the Vatican descended upon the library to take readings, run tests and examine the statue. For two weeks straight, Portland’s hotels were booked solid with the faithful, who lined up to view the statue after the day’s tests were complete.

The hullabaloo had to do with the way in which this little icon threw shadows. Under direct light from a single source, it seemed to the eyewitness that the statue cast three distinct shadows, none of which corresponded to the direction of the light source. Under diffuse light, the shadow seemed to swirl, move and multiply, depending on the angle of the viewer. Adding to the mystery, any attempt to photograph or record the phenomenon failed; the image captured by all manner of cameras, spectrographs and video recording devices would reveal the statue to possess a perfectly ordinary shadow. It seemed that the phenomenon could only be witnessed with one’s own eyes—the “holy shadows” could only be documented by eyewitness accounts.

All the varied and exhaustive tests revealed nothing out of the ordinary in the statue’s physical components or method of manufacture. All sides were at a loss to explain the phenomenon. Scientists compared the mystery of the shadows to Erwin Schrodinger’s quantum thought experiments, while religious philosophers considered the statue to be a fitting metaphor for the ardors of faith.

One scientist took the matter into his own hands. One night, a few days before the Equinox, he stole the statue and boarded a plane bound for Quito, Ecuador. Factoring in the curvature of the earth, the height and width of the icon, and the proximity of Quito to the equator, he had determined the exact moment in time and geographic location whereupon it would be physically impossible for the statue to cast a shadow. It would last a total of 3.2 seconds. Surrounded by cameras, the scientist placed the statue in position and waited.

The outcome of the experiment has never been released to the public, all that is known is that the statue was lost, and the scientist has steadfastly refused to talk about the incident. The film and video recordings of the event were donated to the Vatican, and in what one conspiracy theorist blogger has called “some real Da Vinci Code shit,” they promptly claimed to have lost all the film in a warehouse fire.

As for the scientist, he has kept out of the public eye and has essentially been barred from professional work at most major universities and scientific institutions. “Being black-listed” he remarked, “is a pain in the neck.”

My good buddy and comics-drawing genius, Farel Dalrymple.

A study of pretty, purdy horsies at play in the Presidio